How about a nice cup of tea?

Tea. Combine the dried leaves of a particular sort of shrubbery, a splash of boiling water and – in some instances – a spot of milk to create an elixir beyond compare. This ambrosial liquid punctuates the day, creating little oases of tranquillity in the increasing frenzy of modern British life. Indeed, there is almost no sadder sight than a half full cup of tea. Luke warm (or colder … urgh). Abandoned. Indicative of a life too busy to pause for reflection and a thoroughly enjoyable and gentle caffeine fix. My heart weeps for the poor soul that misses out on the other half of that cup.

For this is the substance that helps bind friends, family and strangers within modern Britain. You know those Olympics we recently held that were a roaring success?

We wouldn’t have done it without tea. FACT.*

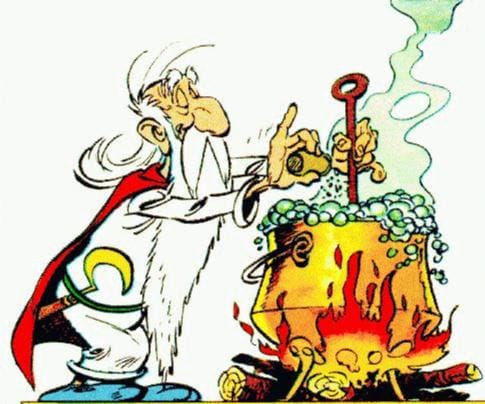

So how did this beverage come to define, nay, forge this nation [cue national anthem gently playing in the background as you read this] and arguably grease the cogs of an Empire? Contrary to popular belief, Getafix the Druid wasn’t the man who introduced tea to these fair isles c. 50 AD.

Getaflix brewing something that doesn’t look quite like tea!

It only really arrived in the 17th century, taking a coffee-obsessed nation by … well, certainly not a storm at first. In 1660 Samuel Pepys wrote “I did send for a cup of tee, (a China drink) of which I had never had drunk before”. His ambivalence is striking, and one wonders if he was simply served an underwhelming cup. I shall return in due course to the importance of tea’s preparation as life has fewer disappointments so great as rubbish tea. Particularly when you’ve paid £2.50 for a cup.

But back to the potted history lesson. With the arrival in 1662 of Catherine of Braganza – Portuguese consort of King Charles II – tea then really did kick off a metaphorical meteorological furore. Merchants had been bringing tea from the East to Portugal for yonks so for Catherine this was standard fare. You can see why she was somewhat miffed when, upon arriving in England to marry said Charles, there was no tea to be had. Only ale.

It’s just not the same. Don’t get me wrong, ale has its place (and a blogpost at some point … I promise!), but first thing upon arrival in a slightly soggy Britain after a long sailing trip across the Bay of Biscay in 1662? Meh. I think not.

Catherine soon changed this worrying state of affairs and within a few months tea was THE trendy drink of choice at court. Soon its popularity spread throughout society. Tea caddies, such as this lovely at the V&A museum, became important household accoutrements for middle class and aristocratic ladies. They were lockable and it was the lady of the house who held the keys, only opening the caddy and brewing the tea herself when guests were in attendance. Imagine Jane Austen doing a Japanese tea ceremony and you’re just about there.

An elegant tea service from the 19th century

The increasing demand for tea also had important economic and political implications. One of the England’s greatest tools of imperialism stepped in to ensure supply met demand. Cue the East India Company and tea flowed into England and the rest of the colonies (Ahem. Best not to mention the Boston Tea Party where things went slightly awry.)

But now a socially awkward situation was brewing (hur hur): If everyone drank tea, how could you distinguish the posh from the hoi polloi? Cue rubbish porcelain tea cups.

First, a scientific aside. For the perfect cup of tea, you need water that is boiling. Not 98 degrees C or 70 degrees C. But 100 degrees C. This is why you’ll never get a decent cuppa on Everest. Water boils at too low a temperature due to the lack of air pressure. FACT.

Now, in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries there were varying levels of quality when it came to tea cups. The wealthy in society could afford the porcelain that wouldn’t crack when boiling water was poured. Those who were poorer couldn’t. And so those with lesser quality cups had to put the cold milk in first before pouring the tea whilst the richer could put the tea in first.

Pretty porcelain tea cups – milk in first or tea in first?

So next time you see someone pouring their milk or tea in first, do have some fun imagining whether their forebears were earls or navvies. Or maybe – as is the case of a chum whose pedigree is beyond question – pouring the milk in first means there’s no need for a tea spoon as the tea then mixes perfectly. And thus there’s one less bit of washing up to do.

Genius.

*Please note that I can provide no evidence whatsoever for this statement but deep down in my bones just know this to be true. It would otherwise have been a shambles beyond compare.

_____________

Zoë F. Willis is a London Perfect reservationist, writer and Londoner. Visit her blog Things Wot I Have Made to find out more about Zoë’s many creative talents!

Photo credits: Two Mugs of Tea by David Martyn Hunt.

[…] about the true power of TEA. You’ve already read the blogposts about the humble leaf’s role in this nation’s imperial expansion, as well as where best to go in London for a high tea of superlative quality and delight. I’ve […]

[…] with accompanying cup and saucer: for without tea, us English are dust. DUST. Don’t tease us about it. And don’t deprive us of it either. […]